When managing multiple products in your digital storefront, it’s essential to create a dedicated product detail page for each item. This strategy is pivotal for furnishing comprehensive information...

Reasons Why

2 min read

People are more likely to adapt their behavior if you give them a reason to do so. Here’s how you can benefit.

How to boost motivation with the Reasons Why principle

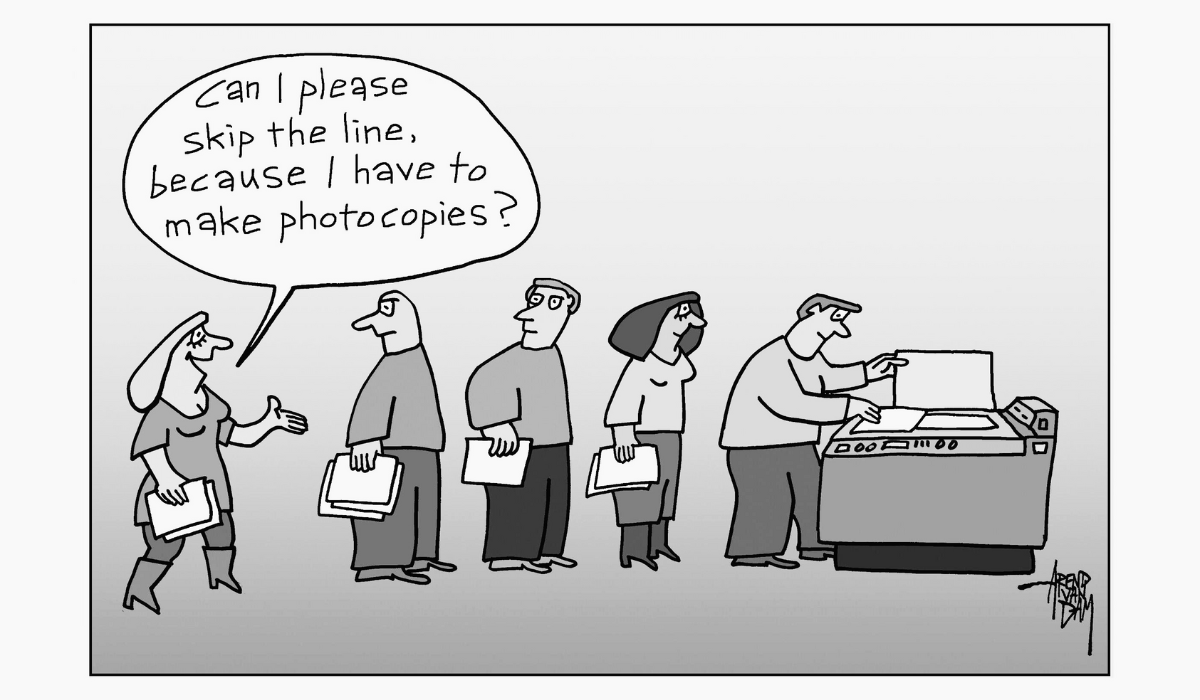

You’re in a hurry for an appointment, and the clock is ticking. Your last-minute task: copy some important documents. But, as luck would have it, there’s a long line of people waiting for the copier. What’s your move? You decide to ask if you can skip the line. Good choice! That is, if you give a reason.

In a groundbreaking study known as the ‘copy machine study,’ Harvard professor Ellen Langer delved into the fascinating realm of motivation and reason.1 She set out to investigate:

- Whether offering a reason could give you priority access to a busy copy machine

- What types of reasons were most effective.

Langer posed the same question to people in the line, but with different variations.

- The first group received a simple request:

“Excuse me, I have five pages. May I use the Xerox machine?” - The second group received the same request, but this time, it came with a compelling reason:

“Excuse me, I have five pages. May I use the Xerox machine, because I’m in a rush?” - The third group received an entirely absurd reason:

“Excuse me, I have five pages. May I use the Xerox machine, because I have to make copies?”

Reasons Why: the results

The results of the copy machine study were eye-opening. When asked the question without any reason, 60 percent of the people allowed the person to go first. However, when a good reason was provided, a staggering 94 percent willingly stepped aside. Remarkably, even when presented with the completely nonsensical reason, 93 percent of those waiting still acquiesced.

Langer’s conclusion was clear: it doesn’t matter what reason you give. As long as you give a reason, you’re more likely to motivate people.

This phenomenon is what we refer to as the ‘Reasons Why principle.’

‘As’ or ‘because’?

You might wonder about the difference between the conjunctions ‘as’ and ‘because.’ Although they have similar meanings, ‘because’ is your best choice if you want to persuade people. Our brains perceive a message after ‘because’ as a fact, while a message following ‘as’ is usually seen as an opinion. As a rule of thumb, facts tend to influence our behavior more effectively than opinions.

Coming up with reasons

So, how can you harness the power of the Reasons Why principle to boost motivation among your audience?

- Start by considering the reasons behind the behaviors you want to encourage. Why would someone download your app, purchase your product or sign up for your newsletter?

- Focus on compelling reasons, as not only will they motivate your audience, but they’ll also genuinely help them make a good decision. Once you’ve identified these reasons, prominently integrate them into your messaging.

Reasons Why: real-life example

Let’s look at the Reasons Why principle in action. We applied this principle successfully to a prominent energy company comparison website. To motivate visitors in their search for an energy provider, we presented the following three reasons:

- Choose this website, because you can save up to $300.

- Choose this website, because wasting money is never a good idea.

- Choose this website, because in just two minutes, you’ll discover your potential savings.

By highlighting these three compelling reasons, we achieved a remarkable 5 percent increase in conversions.

What should you remember?

- People are more likely to adapt their behavior when they are given a reason.

- In principle, the specific reason matters less than the mere presence of a reason.

- Providing a good reason not only motivates, but also genuinely helps your audience.

- This phenomenon is known as the ‘Reasons Why principle.’

What can you do?

- Consider the compelling reasons your audience has for engaging in the desired behavior, and incorporate these reasons into your messaging.

Literature